Highlights of our Work

2026 | 2025 | 2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001

image size:

1.2MB

made with VMD

Everything that living things do can be understood in terms of jigglings and wigglings of atoms.

Richard Feynman's remark in the early 1960's summarizes what is today widely accepted, namely,

that molecular processes can be described by the dynamics of biological molecules, therefore connecting

protein dynamics to biological function. Molecular dynamics (MD) is by far the best tool to investigate

jigglings and wigglings of biological systems. Advances in both software and hardware

have spread the use of MD, however the steepness of the learning curve of the methodology of MD

remains high. To assist new users in overcoming the initial barrier to use MD software, and to help the more advanced users to

speed up tedious steps, we have developed the QwikMD software, as decribed in a recent paper.

By incorporating an easy-to-use point-and-click user interface that connects the widely used molecular graphics

program VMD

with the powerful MD program NAMD,

QwikMD allows its users to prepare both basic and advanced MD simulations in just a few minutes. At the same time,

QwikMD keeps track of every step performed during the preparation of the simulation, allowing easy reproducibility

and shareability of protocols. More information about QwikMD, as well as introductory tutorials are available on our

QwikMD webpage.

QwikMD is available in VMD 1.9.3 or later versions.

image size:

3.3MB

made with VMD

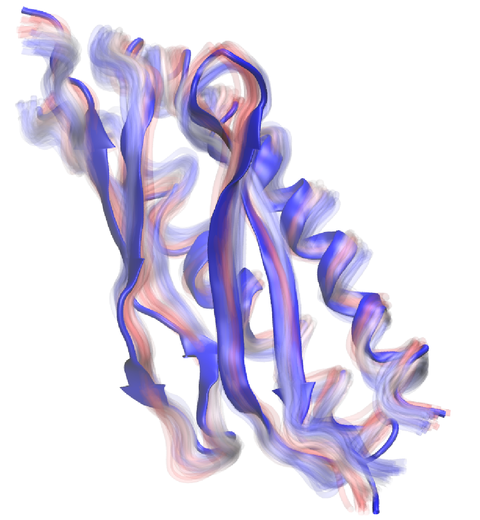

Living cells are brimming with the activity of macromolecular complexes carrying out

their assigned tasks. Structures of these complexes can be resolved

with cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), wherein the complexes are first freeze-shocked into

states characterizing their action and subsequently imaged by detection cameras. Recent

advances in

direct detection camera technology enable today's cryo-EM laboratories to image the

macromolecular complexes at high-resolution, giving us a better view of the cell

than ever before. Computational techniques like molecular dynamics flexible fitting

(MDFF) are a key tool for producing atomic

models of the imaged molecules, providing greater insight into their structure and function.

The increased resolution of EM maps, which contain sharp valleys capable of trapping structures,

presents a challenge to

MDFF which was originally developed for maps in a

lower resolution range.

However, a recent study

unveils two new techniques called cascade (cMDFF) and

resolution exchange (ReMDFF) molecular dynamics flexible fitting to overcome the hurdles

posed by high-resolution maps. The refinement is achieved by interpreting a

range of cryo-EM images, starting with an image of fuzzy resolution and progressively

improving the image's contrast until near-atomic resolution is reached. These techniques

were employed to solve the structure of the

proteasome, the recycling machine of the human cell.

New analysis schemes that look at the flexibility of the obtained structure provide a

measure of model uncertainty within the near-atomic EM images, improving their contrast.

All the tools are

available on cloud computing platforms allowing community-wide usage at low

monetary cost; the complex computations can now be performed at the cost

of a cup of coffee.

image size:

955.8KB

made with VMD

Most life on Earth is powered directly or indirectly by harvesting the energy of sunlight. Plants and bacteria convert solar energy into chemical energy, which is used, ultimately, for producing food. Compared to the complicated energy harvesting apparatus of plants, the primitive purple bacteria display a far simpler instance of photosynthesis. In purple bacteria, the energy harvesting processes are performed by a spherical vesicle, called the chromatophore, featuring hundreds of cooperating proteins assembled together on a membrane. A team of experimental and computational scientists have recently reported the overall efficiency of this energy conversion process based on a structural model. The energy conversion process in the chromatophore shows that the bacteria adapted to efficiently harvest light at the dim light conditions typical of their habitat. At bright light conditions, the bacteria instead dissipate the harvested energy to protect against damage. A step-by-step summary of the energy conversion processes in the chromatophore can be viewed in a video produced by high performance computing (YouTube video; discussed further in article 1 and article 2.) More on energy harvesting by bacteria can be found on our photosynthesis page and the

chromatophore page.

While waste recycling in daily life has become popular only recently,

living cells have been recycling their protein content since

the very beginning. Recycling of unneeded protein molecules in cells

is performed by a molecular machine called the proteasome, which cuts these

proteins into smaller pieces for reuse as building blocks for new proteins.

Proteins that need to be recycled are labeled by tags made of poly-ubiquitin

protein chains. The proteasome machine recognizes and binds to these tags,

pulls the tagged protein close, then unwinds it, and finally cuts it into

pieces. Despite its substantial role in the cell's life cycle, the

proteasome's atomic structure and function still remain elusive. In our

recent

study,

we obtained an atomic structure of the human 26S proteasome by combining

computational modeling techniques,

through molecular dynamics flexible fitting (MDFF) of the cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) data.

The features observed in the resulting structure are important for coordinating

the proteasomal subunits during protein recycling.

One of the key advances is that for the first time the nucleotides

bound to the ATPase motor of the proteasome are resolved.

The atomic resolution of the structure

permits to perform molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the detailed proteasomal function,

in particular the protein unwinding process of the ATPase motor.

Furthermore, our obtained structure will serve as a

starting point for structure-guided drug discovery,

developing the proteasome as a crucial drug target.

The atomic models are deposited in the protein

data bank (PDB) with the PDB IDs 5L4G and 5L4K and the 3.9 Å resolution

cryo-EM density is deposited in the electron microscopy data bank

EMD-4002.

More information about our proteasome projects is available on our

proteasome website. Easy access to our modeling techniques is provided through

QwikMD, which was employed here for the first time.

image size:

1.7MB

made with VMD

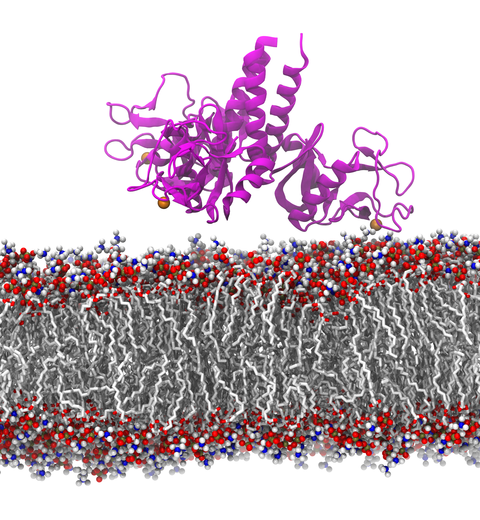

Our lungs are coated with a layer of protein and lipid mixture called lung surfactant, which prevents the lungs from collapsing and protects us from bacterial and viral infections

(see October 2012 and January 2014 highlights).

Lung surfactant protein A (SP-A) - the major protein constituent of lung surfactant -

plays a dual role.

It aggregates DPPC lipid, a major component of lung membrane,

into a lattice-like structure that prevents the lungs from collapsing.

SP-A is also known to recognize and bind bacterial lipids, namely lipid A, on surfaces of gram-negative bacteria,

thereby helping to initiate various clearance mechanisms.

However, it was unclear how SP-A exhibits such functional duality with its binding to two different types of lipids.

A recent study

used molecular

dynamics simulations with

NAMD to unravel the dual role of SP-A.

Combined with crystallographic and mutational analyses,

researchers have discovered several critical, non-canonical lipid binding sites that

involves cation-π interactions and hydrogen bonds.

Simulations have also revealed that SP-A binds stronger to bacterial lipid (lipid A)

than to surfactant lipid (DPPC lipid), which suggests SP-A may prioritize its host defense

functions by transferring from lung membrane to bacterial surface.

These findings in atomistic detail will enable experimentalists to enhance the antimicrobial function of SP-A.

More on our lung surfactant protein website.

image size:

0 bytes

made with VMD

Virus capsids, specialized protein shells that encase the genome of

viral pathogens, play critical roles in regulating viral infection,

and are, thus, of great pharmacological interest as drug targets. In

particular, small-molecule drugs (typically <900 Da) represent a

promising antiviral strategy, and a number of such compounds have been

developed to inhibit virus capsids by interfering with their assembly

and uncoating processes. Importantly, to explain the mechanisms by

which drugs disrupt capsid function, as well as to successfully design

novel therapeutics, the interactions of drug molecules with their

capsid targets must be studied at full chemical detail. Toward this

end, all-atom molecular dynamics simulations are emerging as an

essential technique to investigate the effects of small-molecule drugs

on capsid structure and dynamics. Research presented in a recent Perspective

applying simulations in NAMD

to study drug-bound hepatitis B virus (HBV) and

human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) capsids suggests the types

of valuable chemical and physical information computational approaches

can reveal, and underscores the importance of simulating, not isolated

capsid proteins, but functional assemblies up to the level of complete

capsids.

Notably, through analysis with VMD,

the study found that binding of the drug HAP1 to the HBV capsid

causes global structural changes that subtly alter the overall capsid shape,

including a flattening of capsid curvature. Further, the study found that the

binding of the drug PF74 to the HIV-1 capsid imposes rigidity and causes

shifts in allosteric communication pathways connecting distant regions of the

capsid protein. The authors of the Perspective anticipate that many other such

exciting discoveries regarding virus capsid function and their use as drug

targets lie just ahead on the horizon, and molecular dynamics simulations will

drive these discoveries pending a series of notable advancements in

computational methodology.

image size:

711.1KB

made with VMD

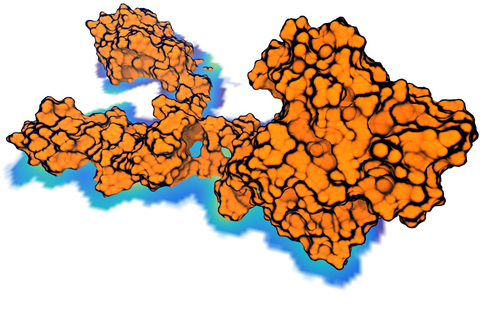

While waste recycling became popular in our daily life, living cells mastered

waste recycling of their protein content since their very beginning. Recycling

of unneeded protein molecules in cells is performed by a molecular machine

called 26S proteasome, which cuts these proteins into smaller pieces and

releases the pieces into the cell interior for reuse as building blocks for new

protein. Proteins that need to be recycled are usually those that are

misfolded. Proteins are recognized as such by the cells' so-called quality

control system. This system labels misfolded proteins by a tag made of

tetra-ubiquitin protein chains. The 26S proteasome machine recognizes and binds

to these tags via its subunit Rpn10. After Rpn10 binds to the tetra-ubiquitin

tag and pulls the protein close, the 26S proteasome unwinds the tagged protein

and cuts it into pieces. A recent

study, based on molecular dynamics simulations with NAMD, sheds light onto how 26S

proteasome and Rpn10 recognize the tetra-ubiquitin tag in three stages: In

stage 1 of the recognition process conserved complementary electrostatic

patterns of Rpn10 and ubiquitins guide protein association; stage 2 induces

refolding of Rpn10 and tetra-ubiquitin tag; stage 3 facilitates formation of

hydrophobic contacts between the tag and Rpn10. More information is available

on our 26S

proteasome website.

image size:

386.7KB

made with VMD

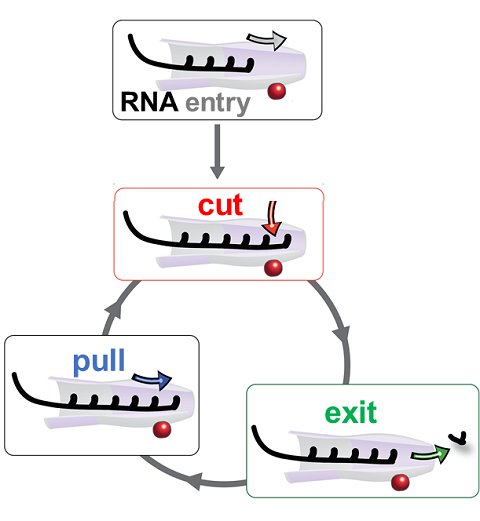

RNA molecules are continuously synthesized in living cells as carriers of

biological information written in the sequence of basic RNA units, called

nucleotides. To keep cells healthy, RNA molecules not longer needed or with

errors have to be removed. A large barrel-like protein complex, the RNA

exosome, is a molecular machine that degrades unneeded RNA molecules, pulling

them inside its long internal channel and cutting them sequentially into single

nucleotides. A new

molecular dynamics study, employing NAMD, shows that a special

active protein subunit of the exosome, called Rrp44, grips tightly the RNA

molecule throughout its extended channel. Rrp44 grips RNA molecules with five

or more nucleotides in length while their ending nucleotides get sequentially

cut, whereas shorter RNAs are only weakly bound and unlikely to be cut. The

simulations reveal how the exosome can act both as a molecular motor that pulls

RNA, without energy input other than the one released in nucleotide cleavage,

as well as an enzyme that cuts RNA. More information is available on our RNA

exosome website.

image size:

101.5KB

made with VMD

When experimental-computational biologists embarked on the great

challenge of resolving the atomic level structure of the HIV virus

capsid that contains the virus' deadly genetic cargo, they were

advised by referees not to try as the capsid is too big, too

irregular, and nobody would need the highly resolved structural

information. Stubbornly, the researchers went ahead anyway and

succeeded getting the atomic resolution structure, overcoming size and

irregularity challenges (see highlight Elusive

HIV-1 Capsid). But the question remained: Is the atomic level

structure of the huge HIV capsid made of 1,300 proteins useless? The

HIV capsid is a closed container made of protein pentamers and

hexamers, with a surface of continuously changing curvature. Two

recent experimental-computational studies demonstrate now that the

capsid structure is far from useless, in fact, it is a great

treasure. The first

study was published last year and showed that the human protein,

Cyclophilin-A (CypA), involved in several diseases, interacts with the

HIV capsid and affects the capsid's dynamic properties (see highlight

HIV,

Cells and Deception). In a second, recent

study, guided by cryo-EM measurements and benefiting from

large-scale molecular dynamics simulations with NAMD, researchers

could resolve with new accuracy the binding of hundreds of CypA

proteins on the capsid's surface. They found that CypA binds along

high curvature lines of the capsid, which enhances stiffness and

stability of the capsid, even though only about half of the capsid is

actually covered by CypA. The limited levels of CypA stabilize and

protect the viral capsid as it moves through the infected cell towards

the cell's nuclear pore where nuclear proteins additionally bind to

the capsid at places not covered by CypA and promote there uncoating

and release of the capsid cargo into the nucleus. More information is

available on our retrovirus website and in

a news

release.

image size:

642.1KB

made with VMD

Motile bacteria position themselves within their habitats optimally, seeking proximity to favorable growth conditions while avoiding unfavorable ones. Cues used for this placement come in the form of small chemicals, so-called attractors and repellants, as well as physical factors such as favorable visible light and unfavorable UV radiation. To balance such a broad range of factors, bacteria monitor their environments and respond by way of a fundamental sensory capability known as chemotaxis. Chemotactic responses in bacteria involve large complexes of sensory proteins, known as chemosensory arrays, that process the information obtained from the bacteria's habitat to determine its swimming pattern. In this sense, the chemosensory array functions as a bacterial brain, transforming sensory input into motile output. Despite great strides in the understanding of how the chemosensory array's constituent proteins fit and work together, a high-resolution description of the kind needed to explore in detail the molecular mechanisms underlying sensory signal transduction within the array has remained elusive. A new study, utilizing cryo-electron microscopy and molecular dynamics simulations with NAMD, reports the highest resolution images yet of the bacterial brain's molecular anatomy. Using computational techniques, structural data from X-ray crystallography and electron microscopy are compared to derive an atomically resolved model of the chemosensory array's extended molecular structure that involves millions of atoms. Subsequent simulations of the model revealed a novel conformational change in a key sensory protein, that is interpreted as a key signaling event in the translation of chemosensory information into swimming pattern. More details on this work can be found in a recent news release as well as on our bacterial chemotaxis website.

image size:

1.7MB

made with VMD

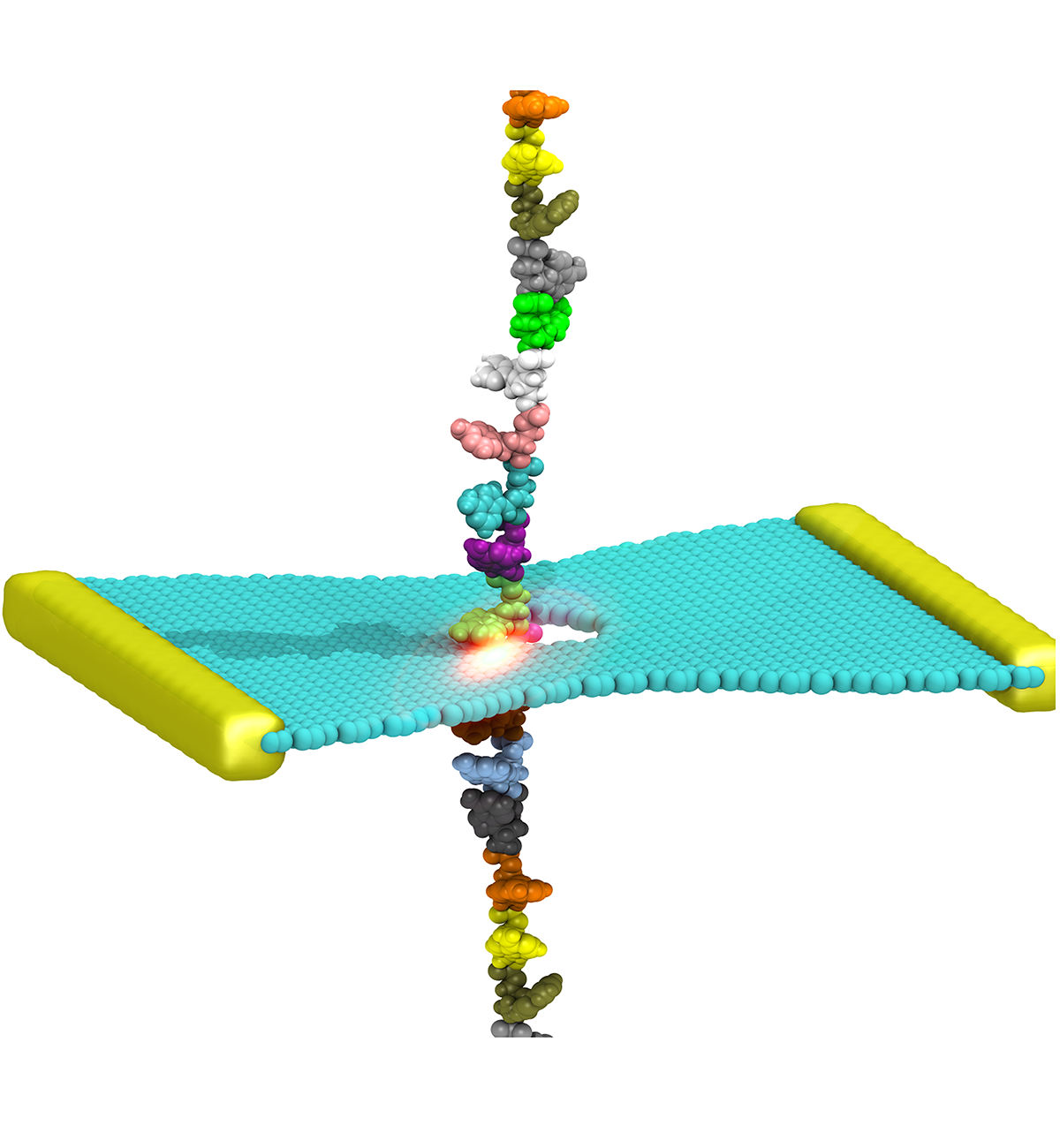

DNA sequencing is achieved by following a strand of DNA at a speed that permits recognition of the DNA bases in their actual order, thousands of bases or more for each pass. Nanotechnology can assist in the task, in principle, by furnishing sensors that can resolve single DNA bases and nano-mechanical actuators that pull the DNA in a controlled fashion passing through the sensor. Instead of building and testing actual sensors and actuators it is cheaper and faster to simulate them. Nanoengineers have indeed succeeded with such simulations over the last decade focussing on silicon technology (see October

2004 highlight: Transistor Meets DNA). Now the engineers have moved with their simulations to graphene technology that promises much better resolving power as sensors are thinner and as signals can be detected electronically in graphene (December

2013 and November

2014 highlights). The main unsolved problem is the mechanical actuator: how can one control movement of DNA through a graphene sensor such that measured signals become less noisy and bases can be recognized? A recent study, based on molecular dynamics simulations with NAMD and quantum electronics calculations of graphene, suggests use of an actuator that simultaneously stretches the DNA and pulls it through the sensor. This manipulation leads to a stepwise translocation of DNA through the graphene nanosensor, slowing down DNA translocation and stabilizing DNA bases inside the sensor. Read more on our graphene nanopore website.

image size:

768.0KB

made with VMD

For centuries, millions of people around the globe have been troubled with a movement disorder that usually starts with a tremor in one hand. The disorder, later known as Parkinson's disease, affects commonly older individuals and disrupts patient's movement, sleep and speech from the brain. There is currently no cure for the disease. Key to the disease, progressively occurring in patient's brain, is the loss of neuron cells due to aggregation of a small protein named α-synuclein. Extensive studies have been carried out, yet the function of the protein remains a mystery. It is amazing that aggregation of such small proteins eventually leads to neuronal cell death and generates tremendous difficulties in peoples' life.

In a recent report, a team of computational scientists attributed the cause of α-synuclein aggregation to a hairpin structure involving just a small region (amino acids 38-53) in the middle of the protein. With extensive simulations (over 180 μs in total), the researchers revealed that a short fragment encompassing region 38-53, exhibiting a high probability of forming a β-hairpin structure, is a key region during α-synuclein aggregation. Moreover, the researchers predicted a mutation that impedes β-hairpin formation, thereby retarding α-synuclein aggregation. The discoveries, made possible through the software

NAMD and VMD, are expected to shed light on the mechanism underlying Parkinson's disease and to inspire the design of drugs. More on our α-synuclein website.