Highlights of our Work

2025 | 2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001

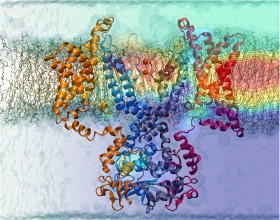

Nerve cells, through their electrical signals, control actions and intelligence of higher organisms. The signals result mainly from potassium and sodium ion channels in the cells: when the cells are stimulated electrically, they send an all (in case of sufficient stimulation) or nothing signal to other nerve cells or organs like muscle. As shown in ground breaking work by 1963 Nobelists Hodgkin and Huxley, cast into mathematical equations, nerve cells establish these signals through voltage gating of channels. The nature of the gating, monitored through the so-called gating current, has been elusive for decades, despite a detailed characterization of the ion conductivity itself rewarded through a 2003 Nobel Prize to MacKinnon. The riddle is that the channel involves a protein with few charged amino acids that seem to be only weakly coupled energetically to an electrical potential gradient across the cell membrane. Now a sweeping modeling study using NAMD employing the most powerful computers available to researchers today has led to an explanation of voltage-gating. Simulations revealed that the potential gradient is focused by the channel protein to a very narrow region such that its value is much larger than anticipated. The protein was also seen to arrange its charged amino acids sensing the gradient in an unusual helix, a so-called 310 helix, that aligns charges perfectly while at the same time inducing a motion that opens and closes the channel. Proof of the veracity of the computational model is that the calculated gating current fits perfectly the observation. More on our potassium channel website.